BEBCRF Support Group Meeting – Toronto, Spring 2011

Psychosocial Aspects of Benign Essential Blepharospasm, Hemifacial Spasm and Cranial Dystonia (Meige Syndrome)

Presenter:

Joanne L. Pilon M.A. (Ed.) Psychotherapist

Thank you for inviting me to speak at your support group meeting. I am a psychotherapist with expertise in treating people with chronic pain and illness as well as stress, anxiety, depression, PTSD and OCD. I became familiar with these conditions while working with Dr. Earl Consky, with whom many of you are familiar, for approximately 10 years while concurrently completing my post-graduate studies. Working with Dr. Consky gave me an interest in chronic illness and I subsequently did my Master's thesis on Cervical Dystonia. This work prepared me well for my career as a psychotherapist and cognitive behaviour therapist at a rehabilitation facility and in private practice.

The prevalence of psychological difficulties in chronic illness is well known, and yet most research on blepharospasm focuses on other aspects such as the causes, assessment, treatment options and treatment outcomes. We can learn from research done about other chronic disorders such as fibromyalgia and blindness to influence our understanding of the psychosocial aspects of this disorder. As well, and perhaps more importantly, what can we learn from each other?

In a perfect world you would have onset of symptoms, be diagnosed accurately by your family doctor, referred to an appropriate specialist in a timely manner, receive effective treatment (in a perfect world, a cure), receive support and understanding from your workplace, friends and family, all with no stress, anxiety or low mood.

Is this anyone's story here? What is more typical is intermittent onset of symptoms, followed eventually by a visit to your family physician. Perhaps eye drops are recommended; perhaps stress or anxiety is suggested. Eventually perhaps there is a referral to a specialist followed by a lengthy wait time.

Blepharospasm, hemifacial spasm and Cranial Dystonia (Cranial Dystonia (Meige Syndrome)) have some unique characteristics that influence the psychosocial problems that may arise including:

- change in physical appearance.

- spasms misinterpreted by others.

- intermittent functional blindness.

- loss of normal function (e.g. driving, reading, work, leisure activities).

- changes in mood due to loss of 'normal' self.

It is normal to feel stressed and anxious during a lengthy diagnosis, during treatment and while living with a chronic disorder. There are strategies to assist you cope with these feelings during this time and while living with blepharospasm, hemifacial spasm or Cranial Dystonia (Cranial Dystonia (Meige Syndrome)).

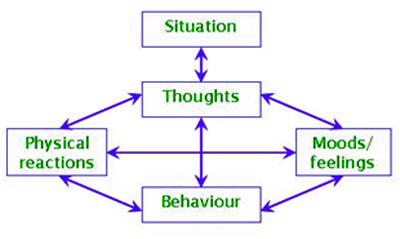

The best recommended approach to manage anxiety, stress and depression is cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT). It is an evidence-based approach that is based on the observation that thoughts, feeling, behaviour and physical reactions are all interconnected. When looking for ways to change how we feel it is often best to focus on changing thoughts, behaviour and physical reactions to influence our feelings.

CBT Chart

For example, the situation is that your doctor tells you that it is going to be six months until you will have an appointment with a neurologist or ophthalmologist. The thought that follows may be "I won't be able to handle the next six months." The feeling is anxiety, fear, sadness, anger. The physical reaction is muscle tension, shortness of breath, rapid heartbeat, shakiness, dizziness which then may lead to thoughts that the illness is getting worse. Behaviour may include social withdrawal, acting out in anger towards loved ones, loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities, changes in sleep, appetite, sexual drive.

We can influence how we feel by changing our thoughts, behaviour or physical reactions. With regard to thoughts, there are ways to think about situations that appear universally negative in a way that is kinder to oneself. Noticing and changing self-talk is useful. With regard to behaviour, using strategies such as relaxation techniques, mindfulness meditation and distraction is helpful and these strategies can also influence our physical reactions.

The first step in challenging your thinking is self-monitoring. You need to become aware of the messages you routinely give yourself. This can be a little more difficult than it might first appear. The negative messages tend to be so automatic and routine that we may not even be aware of them. Usually, you can quickly identify the activating event and the emotional consequence - you know what has happened and how you feel - but identifying the thoughts and beliefs that lead to the emotional consequence can be more challenging. You would next fill out a thought record. (Download Thought Record Sheet PDF here.).

All-or-Nothing Thinking

This type of distortion is the culprit when people think in extremes, with no gray areas or middle ground. All-or-nothing thinkers often use words like "always" and "never" when describing things. "I always get stuck in traffic! "My bosses never listen to me!" This type of thinking can magnify the stressors in your life, making them seem like bigger problems than they may, in reality, be.

Overgeneralization

Those prone to overgeneralization tend to take isolated events and assume that all future events will be the same. For example, an over-generalizer who faces a rude sales clerk may start believing that all sales clerks are rude and that shopping will always be a stressful experience

Mental Filter

Those who use mental filtering as their distortion of choice tend to gloss over positive events and hold a magnifying glass to the negative. Ten things can go right, but a person operating under the influence of a mental filter may only notice the one thing that goes wrong. (Add a little overgeneralization and all-or-nothing thinking to the equation, and you have a recipe for stress.)

Disqualifying the Positive

Similar to mental filtering, those who disqualify the positive tend to treat positive events like flukes, thereby clinging to a more negative world view and set of low expectations for the future. Have you ever tried to help a friend solve a problem, only to have every solution you pose shot down with a "Yeah but..." response? You have witnessed this cognitive distortion firsthand.

Jumping to Conclusions

People do this one all the time. Rather than letting the evidence bring them to a logical conclusion, they set their sights on a conclusion (often negative), and then look for evidence to back it up, ignoring evidence to the contrary. The kid who decides that everyone in his new class will hate him, and 'knows' that they are only acting nice to him in order to avoid punishment, is jumping to conclusions. Conclusion-jumpers can often fall prey to mind reading (where they believe that they know the true intentions of others without talking to them) and fortune telling (predicting how things will turn out in the future and believing these predictions to be true). Can you think of examples of adults you know who do this? I bet you can.

Magnification and Minimization

Similar to mental filtering and disqualifying the positive, this cognitive distortion involves placing a stronger emphasis on negative events and downplaying the positive ones. The customer service representative who only notices the complaints of customers and fails to notice positive interactions is a victim of magnification and minimization. Another form of this distortion is known as catastrophizing, where one imagines and then expects the worst possible scenario. It can lead to a lot of stress.

Emotional Reasoning

This one is a close relative of Jumping-To-Conclusions in that it involves ignoring certain facts when drawing conclusions. Emotional reasoners will consider their emotions about a situation as evidence rather than objectively looking at the facts. "I'm feeling completely overwhelmed, therefore my problems must be completely beyond my ability to solve them," or, "I'm angry with you; therefore, you must be in the wrong here," are both examples of faulty emotional reasoning. Acting on these beliefs as fact can, understandably, contribute to even more problems to solve.

Should Statements

Those who rely on 'should statements' tend to have rigid rules, set by themselves or others, that always need to be followed -- at least in their minds. They do not see flexibility in different circumstances, and they put themselves under considerable stress trying to live up to these self-imposed expectations. If your internal dialogue involves a large number of 'shoulds', you may be under the influence of this cognitive distortion.

Labelling and Mislabelling

Those who label or mislabel will habitually place labels that are often inaccurate or negative on themselves and others. "He's a whiner." "She's a phony." "I'm just a useless worrier." These labels tend to define people and contribute to a one-dimensional view of them, paving the way for overgeneralizations to move in. Labelling cages people into roles that do not always apply and prevents us from seeing people (ourselves included) as we really are. It is also a big no-no in relationship conflicts.

Personalization

Those who personalize their stressors tend to blame themselves or others for things over which they have no control, creating stress where it need not be. Those prone to personalization tend to blame themselves for the actions of others, or blame others for their own feelings.

If any of these feel a little too familiar, that is a good thing: recognizing a cognitive distortion is the first step of moving past it.

Next you challenge the evidence. Is there any evidence that supports the thought? Is there any evidence that does not support the thought? For example, if you are fortune telling it has not happened yet. If it is a 'should' statement you may change your thought to 'could' or 'may have', as this is less emotionally loaded.

The alternative or balanced thoughts could be "I'll take it one step at a time." "I've been through difficult situations before, I can go through this."

Even if a situation seems universally negative there are ways that we can be kinder to ourselves.

You next do a 'cost-benefit' analysis. (What are the advantages and disadvantages of these thoughts or behaviour? Having gone through this exercise what rate might your feeling be? Usually people go from an 8 to 4 out of 10 or a 7 to 3 by doing this exercise.

As best you can, try to ensure that you have an outlet for your feelings. This may include talking with a friend, family members, support group or seeking professional help.

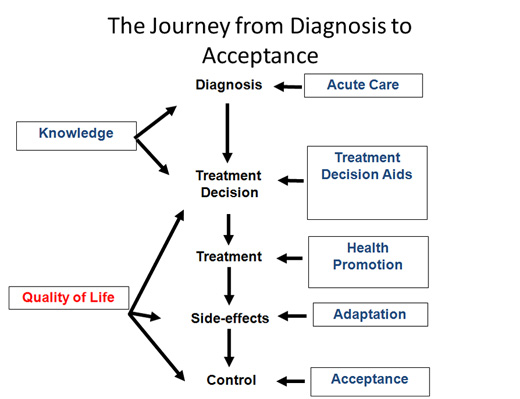

Below is a diagram showing the journey from diagnosis to acceptance.

Chart to Acceptance

You will notice that I have highlighted in red "Quality of Life." What constitutes quality of life is very individual. For example, if reading is your favourite past-time, then finding ways to enjoy literature will be an important goal. If going for walks is important, then trying to find ways to maintain this activity will be important. People get "stuck" when they focus on the past and what they have lost rather than what they can accomplish in the present. Focusing on the past can lead to depression. Focusing on fear of the future can lead to anxiety.

Oftentimes there are stages that a person goes through before reaching the acceptance stage. Difficulties occur when you get stuck at one or more of these stages. You may identify with one or more than one of these stages. Even talking about these stages is a way of acknowledging and validating your feelings.

Stage 1: Fear and Concern

What is wrong with my body? When will I return to 100 %? What will happen to my future?

Stage 2: Denial

You have been diagnosed with a chronic neurologic condition. You avoid doing anything physically or psychologically to help your condition. You focus your efforts on how others can help you rather than how you can help yourself.

Stage 3: Frustration and Depression

You realize that despite medication and injections your symptoms may still be present. You become frustrated and angry that nothing is getting rid of the problem. You isolate yourself and become irritable and impatient. You fixate on the past and worry about the future.

Stage 4: Hopelessness and Passivity

You become demoralized. You ask yourself, "What did I do to deserve this." "Why did my life have to change?" You start to feel sorry for yourself and angry about the situation. You focus on things that you cannot change.

The stages that people go through working towards the final stages of acceptance are similar to that with grief and loss.

Getting a life-changing diagnosis for some people is experienced as a traumatic incident and as such some people may be subject to a post-traumatic stress response. These are normal responses that occur under abnormal circumstances. Some examples are shock, denial, disbelief, anger, fear and questioning of spiritual beliefs. Receiving this diagnosis may also trigger a grief response requiring mourning. Mourning can initiate a broader range of feelings such as:

- a search for the meaning of illness.

- a "life review".

- a search for the meaning of life.

Stage 5: Acceptance

You come to accept that there are real changes that you must learn to live with. However you do not resign yourself to staying the same, but you continue to find ways to improve yourself. You focus on the positive and achievable, not the negative and impossible. You come to accept that there are real changes that you must learn to live with. However you do not resign yourself to staying the same, but you continue to find ways to improve yourself. You focus on the positive and achievable, not the negative and impossible. You understand that this is a process of daily renewal. You go on to live a meaningful and productive life. The benefits of acceptance are:

- preservation of one's self-concept

- an ability to engage in life with new conviction.

- an ability to live more effectively in the present.

- a renewed and balanced attempt to find meaning in life.

Mindfulness Meditation

Mindfulness Meditation is the practice of being in the here and now without judgment, noticing each thought and feeling as they arise. It is recommended to start with a sitting meditation for three minutes, five times per day – then increasing gradually to 20 minutes at least once per day.

Why Mindfulness?

Anxiety issues root from the fact that people are worried about the past or the future. Mindfulness grounds us in the moment – there is just this moment, nothing else is happening.

Mindfulness assists us in slowing down, allowing us to relax our minds and muscles. It is a natural antidote for the tenseness and racing thoughts that arise due to anxiety.

Mindfulness allows us to observe internal processes and external events as they unfold, without attachment to outcomes. It reduces reactivity to events and distress.

Mindfulness of the Breath Exercise

Settle into a comfortable sitting position on a straight-backed chair. It is very helpful to sit away from the back of the chair so that your spine is self-supporting.

Allow your back to adopt an erect, dignified and comfortable posture. Place your feet flat on the floor, with your legs uncrossed. Gently close your eyes or gaze softly downwards.

Bring your awareness to the level of physical sensations of touch and pressure of your body where it makes contact with the chair. Spend a minute or two exploring these sensations.

Bring your awareness to the changing patterns of physical sensations in the lower abdomen as the breath moves in and out of your body.

Focus your awareness on the sensations of slight stretching as the abdominal wall rises with each in-breath, and of gentle deflation as it falls with each out-breath. As best as you can, follow with your awareness the changing physical sensations in the lower abdomen all the way through as the breath enters your body on the in-breath and all the way through as the breath leaves your body on the out-breath, perhaps noticing the slight pauses between one in-breath and the following out-breath.

There is no need to try to control the breathing in any way – simply let the breath breathe itself. As best you can, also bring this attitude of allowing to the rest of your experience. There is nothing to be fixed, no particular states to be achieved. Simply allow your experience to be your experience without needing it to be other than this. Notice as your mind wanders away from the focus on the breath in the lower abdomen to thoughts, planning, daydreams or other things. This is perfectly ok – it is simply what minds do. When you notice that your awareness is no longer on the breath, gently congratulate yourself – you have come back and are once more aware of your experience. Gently escort the awareness back to a focus in the changing pattern of physical sensations in the lower abdomen, renewing the intention to pay attention to the ongoing in-breath and out-breath.

However often you notice that the mind has wandered, gently congratulate yourself each time on reconnecting with your experience and bring your attention to the breath.

As best as you can, bring a quality of kindliness to your awareness; perhaps seeing the repeated wanderings of the mind as opportunities to bring patience and gentle curiosity to your experience.

When you are ready, wiggle your fingers and toes and gently bring your awareness back to the room.